Political Violence: A Pocket Guide

Over the last week, my feed has been full of people falling over themselves to reassure everyone they know of their core belief that:

political violence is always wrong.

Of course, there are some obvious parameters for this sweeping statement. What I think people generally mean is that they believe that political violence by non-state actors is always wrong. That is, they believe that the state’s monopoly on violence should be sacrosanct. My reasoning for that is that the people making these kinds of statements aren’t also arguing for things like defunding the police and prison abolition, so they are clearly making a distinction between violence by state actors and non-state actors.

Problem is, many of these folk seem more than a little unprepared to wade into a philosophical discussion about violence. The most obvious criticism of this idea that non-state political violence is always wrong is to point to times in the past where it seemed like it, well, it might have been a good idea.

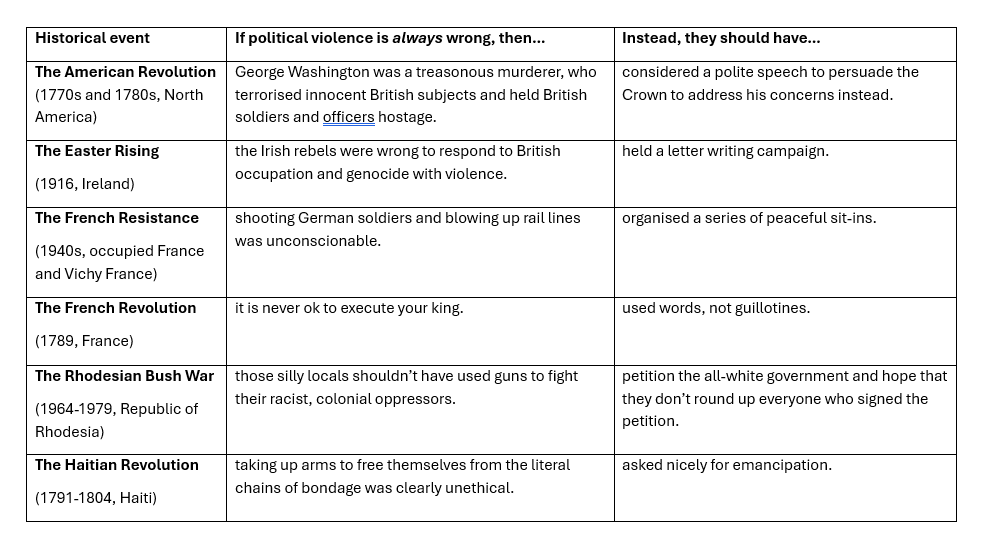

To help newbies in this discussion defend their absolutist idea, I’ve produced a quick reference guide of six well-known historical examples that critics may cite as examples of where non-state political violence was good, actually - and what you can say in response.

Now, if you’re feeling like those arguments aren’t for you, then maybe it’s time to reconsider whether you really believe that non-state political violence is always wrong, or whether there might be some more nuance to this one.

And probably far more importantly, it’s time to think about political violence done by states. Because if you’re an American and you don’t care for political assassinations committed by state actors, I’ve got some bad news for you.